Hello everyone!

Update: My updated 12-tone pattern book is out! I want to give you a precursor by showing you a cool approach to working 12-tone ideas into your playing. This is a really long lesson because it’s tough to distill 200+ pages of material into a web post, but just take it in bite sized chunks and come back to it as you need to and I’m sure you’ll get something from it.

First, a little bit about the book!

The physical book and the e-book pdf are available on Lulu.com or on Amazon.com (or any of the international Amazon sites).

Symmetrical Twelve Tone Patterns is a 284 page book with a large reference component and about 100 pages of extensive notated examples and instruction.

What makes this book different (apart from the cover) and what I’m most excited about offering is a bundle of files that will help readers maximize material in the book. The bundle contains:

-

Guitar Pro files of all the examples in the book (in GP6 and GP5 format). For those of you unfamiliar with this musical notation, tablature platform and playback program, having Guitar Pro files means that the reader can hear the examples without having a guitar handy and can work as a phrase trainer to help the reader get the examples to up to speed.

- MIDI files of the musical examples.

- PDFs of the musical examples.

- MP3s of all the musical examples (again, exported from the same material).

Symmetrical Twelve-Tone Patterns presents 12-tone patterns in both improvisational and compositional contexts. It shows how to create various intervallic lines and creates the outline of a tune and dissects how all the parts were created using this method. If you’re looking for ways to explore new avenues in playing or in your writing this is the book for you!

.

Fire up the video game

When I heard the Praxis Transmutation (Mutatis Mutandis) record, I was blown away with Buckethead’s playing. It also came at a time that I was getting into a lot of 12-tone music and trying to figure out how to adapt those things to guitar and his intervallic/atonal tapping ideas in particular seemed to go in a completely different direction that the 12-tone ideas I heard Jason Becker and Marty Friedman throw into their playing.

Public Service Announcement (i.e. a brief note about playing out):

Playing out just means playing note choices outside of a given tonality. By its very nature, playing out requires an ability to play “in” because it requires a contextual contrast. So my suggestion is that you make sure you develop your ability to play in a tonality as well as outside of it. (Also as a FYI – playing out is easy, but musicians are often judged by how musically they get back in).

.

Every once in a while, I get a hankerin’ for what I call “video game licks” (or symmetrical interval legato licks with a lot of gain and an unclear harmony). Shawn Lane could veer into that territory when he wanted to but for me, Buckethead is pretty much the king of this approach.

In the lick below, I’ve worked all 12 tones into a two-handed idea that uses pick and fret hand tapping. I’ve kept it short so that you can focus on the coordination between both hands, but I’ve included a longer version of the lick after it. As the lick uses all 12 tones, it doesn’t belong to any one key so try playing it over various chords or riffs of your choosing.

.

Technical Notes:

- If you want to get this lick under your fingers, pay attention to the 3 T’s (hand tension, timing and tone) as you practice this.

- Try to make sure that the motion from the fingers for striking the strings comes from the large knuckle of the hand (for more information on this see the glass noodles post).

- The pattern is a variation on the tapping figure Greg Howe uses in kick it all over. It’s written in groups of 6 to fit into one bar – but just practice it slowly as triplets to get the initial speed and coordination down.

- I never got into muti-finger tapping on phrases like this one (I just use the middle finger of the picking hand while I hold the pick with the index finger and thumb), but using the ring, middle and first finger on the picking hand for the upper register tapping you could probably work the phrase up to a tempo 30 bmp faster than this one.

.

.

Short lick faster

.

Short lick slower

.

Here’s an extended variation that moves the fingering pattern to the B and D strings. While the pattern doesn’t keep all of the same intervals as the first example, it has enough continuity to sound like the same 12 tone idea. One recommendation I have is not to get into the dogmatic practice of having to use all twelve tones. If 10 notes work well, use ten notes. In any process like this, use the rules that work for you and discard the rest.

While not notated, this pattern uses all of the same fingerings and note attacks as the first example.

.

.

Longer lick faster

.

Longer lick slower

.

Here’s how I’m visualizing this and how you can generate a lot of ideas from this one approach.

.

The 12-tone pattern vs the 12 tone row

When I first got into 12 tone music and tried to think of a way to incorporate it into improvising, I grabbed some Webern and Berg tone rows (in an over-simplified description – a tone row is a restructured chromatic scale that is used for melodic and harmonic material) and tried improvising with them.

It was pretty dismal.

I found them really hard to improvise with because the row material was difficult to memorize and the number of notes made it difficult to use in an improvisation and then I thought about generating 12-tone patterns instead of working with rows.

.

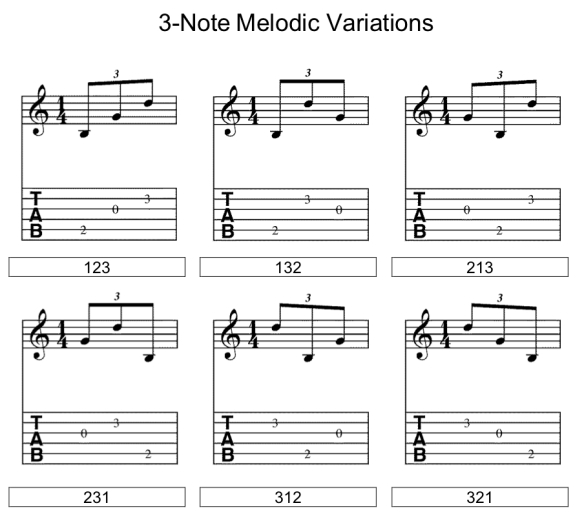

Patterns can be useful in improvisation because:

- they can be used to generate motifs, or themes

- they can be manipulated in real-time and

- they can establish recognizable elements of control in an improvisation.

The other advantage of a pattern is that its intervallic consistency adds an internal drive to melodic ideas. The notes of the pattern move in and out of various tonalities, so it sounds “out” but not random (although you can modify it to be as random as you’d like.

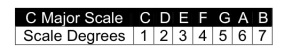

In the 12 tone pattern book I wrote, I used a chromatic scale as a template for generating symmetrical patterns for improvisation. Intervallically uniform, the 12 notes of the chromatic scale are evenly divisible by the numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12. Since divisions of 1 and 12 do not divide the row into a more useable set, they can be ignored. This leaves:

.

6 equal divisions:

(of a descending chromatic scale staring on C)

C B / Bb A /Ab G /Gb F / E Eb / D Db

Taking the first note of each division gives us:

C, Bb, Ab, Gb/F#, E, D

aka: Whole tone scale (any note root)

.

A 12-tone pattern can be created by putting notes in between the notes of the whole tone scale. Note that the intervals between all the 2-note divisions are symmetrical.

.

C B / Bb A /Ab G /Gb F / E Eb / D Db

C A / Bb G /Ab F /Gb Eb / E Db / D B

C G / Bb F /Ab Eb /Gb Db / E B / D A

C F / Bb Eb /Ab Db /Gb B / E A / D G

C Eb/ Bb Db /Ab B /Gb A / E G / D F

C Db/ Bb B /Ab A /Gb G / E F / D Eb

.

One advantage to symmetrical patterns is that they work off of divisions you probably already know. If you can visualize a whole-tone scale, for example, filling in the other notes of the pattern becomes relatively easy.

.

4 equal divisions of the row:

C B Bb /A Ab G / Gb F E / Eb D Db

aka: C, Eb, Gb, A (Bbb)

aka: Diminished 7 chord (any note root)

.

3 equal divisions of the row:

C B Bb A /Ab G Gb F / E Eb D Db

aka: C E G#

aka:Augmented triad (any note root)

.

2 equal divisions of the row yields:

C B Bb A Ab G / (Gb/F#) F E Eb D Db

aka: Tritone interval either note could be root

.

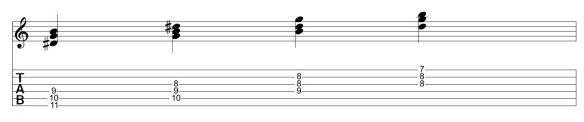

Using the divisions to create a 12-tone pattern

Here’s how I came up with the original example. Using a diminished 7th chord as a starting point, the rest of the twelve tones could be filled in by playing three additional notes off each chord tone. Let’s say you have D diminished 7th chord (since any note in a diminished 7th chord can be a root it’s also a B, F and Ab diminished 7th chord).

.

B D F Ab

.

By adding 3 notes not already in use to each starting pitch you can create a 12-tone row. If you work out the same intervals on these notes you get a symmetrical twelve-tone pattern.

B (Perfect 5th down) E, (minor 2nd down) D#

D (Perfect 5th down) G, (minor 2nd down) F#

F (Perfect 5th down) Bb, (minor 2nd down) A

Ab (Perfect 5th down) Db, (minor 2nd down) C

.

Adapting it to guitar

Where this gets cool part 1:

If we restructure the order of the first notes we get two tritones a minor 3rd apart. Since the E and G strings are a minor 3rd apart this means that the fingering pattern will be the same on both sets of strings.

.

.

Where this gets cool part 2:

As I’ve mentioned before, using standard tuning the guitar can be visualized as three sets of strings tuned in 4ths. So this means that the same fingering can be used to generate the same intervals on the G and D strings.

.

.

From here, you can see where the approach for the first lick came from.

.

.

Taking it further

.

Another nice thing about patterns is that they’re easy to manipulate and draw other ideas from. Let’s take a look at the first 12 notes:

.

You can change the last four notes to create new lines.

.

.

Here are these two ideas in notation and tab.

.

.

You could apply the same two-handed idea we’ve been looking at to any of these patterns or, better yet, apply your own!

.

Here are the last two patterns starting with F-Bb

.

.

The next step is to change the middle notes of the pattern.

.

.

This creates 4 new patterns that start with F-E-A, F-E-Eb/D#, F-E-C and F-E-F#.

.

.

.

Here’s the same idea applied to F-C#/Db

.

.

.

.

And finally, patterns starting with F-G.

.

.

.

.

To sum up, that’s 16 very different licks all pulled from one approach and one initial pattern. This is really the tip of the iceberg for this concept but as you can see, you really don’t need more than one approach to get the ideas flowing and use them on your own.

.

Note:

Sometimes you get an idea and think that you’re doing something unique. You get all excited about it until (if you’re me) you realize that Dave Creamer addressed many of these points back in the June 1989 issue of Guitar Player. Dave’s article inspired me to continue to research this book and try to present similar material my own way.

.

* (I should also mention in passing that (with the better part of a year’s worth of research) – The GuitArchitect’s Guide to Symmetrical 12-Tone Patterns shows all possible symmetrical patterns for the 2, 3, 4 and 6 note divisions above.)

.

I hope this helps and thanks for reading!

-SC

.

The physical book and the e-book pdf are available on Lulu.com or on Amazon.com (or any of the international Amazon sites)

Symmetrical Twelve Tone Patterns is a 284 page book with a large reference component and about 100 pages of extensive notated examples and instruction.

What makes this book different (apart from the cover) and what I’m most excited about offering is a bundle of files that will help readers maximize material in the book. The bundle contains:

-

Guitar Pro files of all the examples in the book (in GP6 and GP5 format). For those of you unfamiliar with this musical notation, tablature platform and playback program, having Guitar Pro files means that the reader can hear the examples without having a guitar handy and can work as a phrase trainer to help the reader get the examples to up to speed.

- MIDI files of the musical examples.

- PDFs of the musical examples.

- MP3s of all the musical examples (again, exported from the same material).

Symmetrical Twelve-Tone Patterns presents 12-tone patterns in both improvisational and compositional contexts. It shows how to create various intervallic lines and creates the outline of a tune and dissects how all the parts were created using this method. If you’re looking for ways to explore new avenues in playing or in your writing this is the book for you!

I like physical books and the softbound version looks really good on my music stand – but I understand that some people like pdfs. The softbound copy GuitArchitect’s Guide To Symmetrical Twelve-Tone Patterns is $35 (though it’s currently selling for $31.50 on Amazon) and the e-book pdf is $15. Both are available from The GuitArchitecture Product page on Lulu.