“It’s been a long…long…time”

I just realized that it’s been a while since I posted anything here. Life has a habit of getting in the way of well laid plans. So here’s a bullet point list to create a quick update.

- Korisoron – We are currently working on a new KoriSoron recording and our most intensive material will be on this one! Initial tracking is in progress and we expect to have the recording out in September. I’m also writing new material for the project and- Booking new gigs for the fall.

- TEDx – Korisoron has been asked to perform at TEDx Schenectady this fall and I’ll be delivering a related talk.

- Old Project – I don’t want to jinx anything but I should be getting together with some former band mates of mine and putting some finishing touches on a project that was very near and dear to my heart (and that I’ve mentioned in prior posts). Fingers crossed – that will be another EP out this fall.

- “Eel-Ech!-trick-a-coup-stick” – is the tentative title of a solo acoustic recording I’ve been working on. I had previously recorded some tracks but wasn’t happy with them so I’ve been cleaning some things up and moving forward with getting that out the door by the end of the year.

- The new pedagogy approach I mentioned a while back – I’ve been working on this but, quite honestly, I seriously underestimated the amount of prep I’d need to do to make this work so I’m just rolling up my sleeves and trying to pull ahead. I took some notes back from the presentation I did at the HVCC Guitar Festival and have been pulling the material together – but I’ve learned more in the last 6 months about how to deliver everything (and what to deliver) than I learned in all my previous years. I’m super excited about what this is becoming.

- The other things – I have a few other musical things in the works that are too tentative to discuss, but, well, let’s just say that it’s a lot of electric guitar in various fashions that will be disruptive. Other things also include a lot of revision plans for this site as well.

A lesson while you’re waiting

One of the things that hold up posts are the fact that I don’t write them in an organized way. I write them in real time based on a theme in my head because it makes the writing more immediate and (hopefully) engaging for the reader. Good for the reader – bad for productivity. A post with any kind of lesson content typically takes 3-5 hours but some of the mode ones took 10-12 hours in editing, layout etc. so that’s why the posts get a bit sporadic for actual lesson material.

The value of recycling

One trap I still find myself falling into is the trap of “short attention span theater” or playing an idea, discarding it like a child’s toy and then picking up another idea and doing the same. Maybe it’s a little cultural ADHD kicking it – but it’s very easy to loose site of taking a theme and really developing it into something. (A great example of this for me is Bill Frissell’s Nashville where you can really hear each of the players take care in developing musical solos based on the melody).

From a technical standpoint, this approach can also be really useful. It can take a long time to really master technical aspects of performance (particularly at the early stages). Finding new ways to utilize the approaches you’ve been practicing will dramatically reduce the time it takes to learn new things. For example, alternate picking takes a long time to develop at the early stages of playing, but once you have it down it makes everything you have to lean to play with alternate picking easier to perform.

Optimize

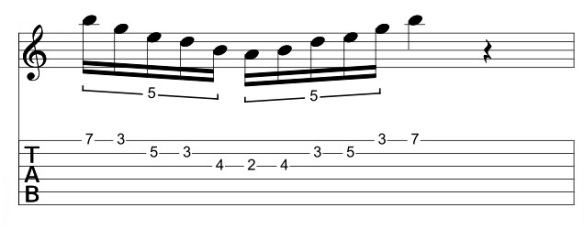

Let’s take an A minor pentatonic lick.

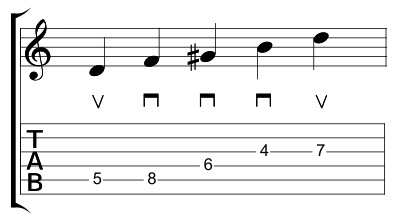

Let’s say that you’re using hammer ons and pull offs to create a more legato feel.

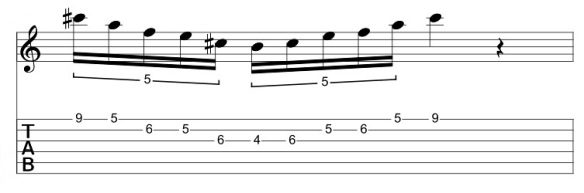

For me, the most legato part of this passage is the last three notes. I’ll move the E on the B string to the 9th fret of the G string to put 3 notes to that string and make the pattern more fluid.

(Note the change in fingering)

This is more of how I approach pentatonic fingerings so I adapted the first fingering for one that works better for me. Here’s the first part of the lesson – assuming that you have a base level of technique acquired – find fingerings that make sense for you!

If this fingering isn’t one that’s common for you and you want to practice the approach. Here’s how I would do it.

1. Isolate. There are two technical hurdles in this lick. Combining the 1 note per string and 3-note per string notes with picking

And this:

And this:

And the transition between the two:

2. Practice

The first step is to just get the initial fingering and picking down.

- Set a metronome for 5-10 minutes.

- Slow it down! Playing fast before you’re ready just adds tension and makes the lick sloppier and harder to play. The goal is to take something you can play perfectly and effortlessly and then systematically develop it so you can play it perfectly and effortlessly faster.

- Pay attention to the 3 T’s (Timing, Tone and hand Tension). If you find your attention wandering this will get it back. Are there any biffed notes? (Watch that pinky!) Is any part of the hammer-on/pull-off uneven? (Bonus credit – make a video recording and listen back. Pay attention to what both hands are doing. Be critical but not judgemental. Imagine you are watching a friend play this. What constructive criticism could you add to help him or her play it better?)

- Write down what you just did.

- Adapt this to the second lick and the transitional lick if need be. Get it to the point that the entire lick can be played without mistakes.

- Repeat as long as time allows. Do daily (and if possible, multiple sessions daily).

- Typically with something like this, I’ll also practice it as sextuplets and a few other rhythmic variations to have those at my disposal if need be.

3. Extrapolate.

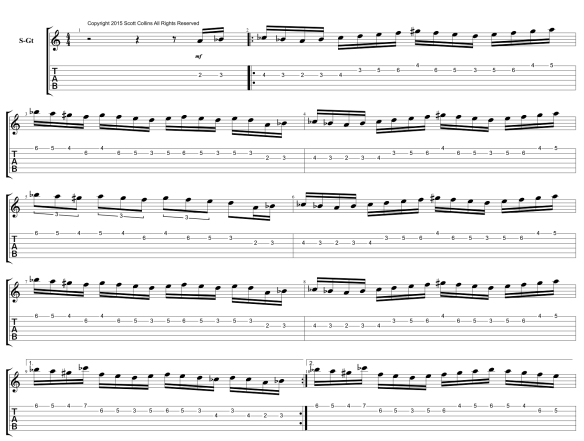

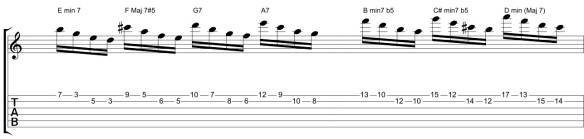

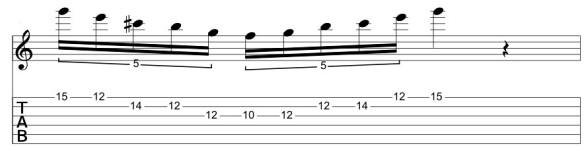

This is something I improvised over a C minor-ish feel that uses the same technical approach that I used on the previous lick with a C Blues scale.

Click on image to see a larger version

From a technical standpoint – this is the same basic idea as the first 6 notes from the previous A minor example.

(Ah – the fingering is missing here – I’m using 2-1-2-3 for each of these)

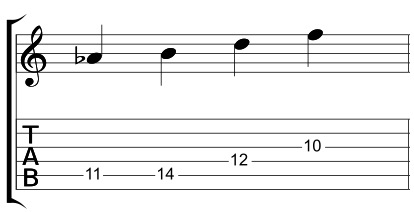

Sequenced here from the b7:

And from the 5th here:

In fact the only new thing is the string skipping at the end:

(I got lazy here – I’m using the tritone F#/Gb interchangeably).

If the string skipping is unfamiliar to you you can just use the same approach to get it down outlined above.

(Yet another) Shawn Lane Observation

I was watching some footage of Shawn Lane that someone posted the other day and this technical recycling was VERY apparent to me in the footage. From a technical standpoint, it appears to me that he took six or seven technical approaches beyond the realm that anyone else was willing to develop them to (fretting hand taps as opposed to hammer-ons, rhythmic groupings variations (5,6,7,9, etc), wide interval string skipping, Hindustani / Carnatic slide playing and blues phrasing) and adapted those to all of the different music he was engaged in.

In Karate, it always comes back to the Kata. In boxing – the basics, the jab, the hook, cross, the uppercut. You can practice fundamentals your whole life and STILL find things to improve. New techniques take a long time to get down. Invest the time wisely to get the one’s you need REALLY down to help realize what you want to express and then explore your sonic world with the tools you’ve developed. (and if you’re not sure which techniques those are – a good teacher can help! You can email me at guitar (dot) blueprint at gmail if you’re interested in setting up skype lessons to help realize your goals.)

As always, I hope this helps!

Thanks for reading,

SC