Hello everyone!

.

I wanted to post a lesson up that uses one of my approaches to harmonizing scales from my Harmonic Combinatorics book. It’s a cool way to not only get away from stock voicings but also to generate new lines as well!

I’m using C Major as the tonal center for this lesson but the approach can (and probably should be) be adapted to any scale.

.

A couple of lessons ago, I talked about the modal microscope – which was a term I used to discuss examining modes on multiple levels and the advantage of viewing modes as subsets of a parent scale. Before I get into the harmonization approach I want to expand on this idea of the microscope analogy and apply it to harmony.

.

The Harmonic Microscope

If I harmonize a parent major scale in the key of C, I’ll end up with the following chords on each scale degree.

.

.

So if you’re playing in the key of C and want to get into more harmonic depth on an E minor chord, it’s time to reach into your chord bag and pull out your stock minor 11 (b9, b13) voicing. Oh, you don’t have one? Don’t worry – most guitarists don’t. Learning stock voicings and inversions for this specific chord form probably isn’t the best use of your time anyway.

Using the microscope analogy, this is really looking at the chord on a 2x setting.

.

Here’s the 1x setting for this example:

playing any combination of the notes from C Major over the root E creates some variant of an

E min / min7 / min7 (b9) / min 11 (b9, b13) chord.

.

And here’s the bigger picture:

Once you are aware of the types of sounds that are created from various chord types, you can start thinking about chords and chord voicings on the macro (i.e. parent scale) level. This means that if I’m playing over a D minor chord and using notes from the C major scale, I don’t have to analyze each indidual chord because I know it’s all under some type of generic D minor 7/minor 9/minor 11 or minor 13 umbrella.

.

Harmonic Combinatorics

Harmonic Combinatorics refers to a process of identifying “countable discrete structures” harmonically. In other words, it examines unique combinations of notes on all of the possible string combinations for the purposes of develop harmonic and melodic possibilities. One way to do this is through a method that I use to generate unique ideas through a process that some people refer to as spread voicings.

.

A Systematic Method For Harmonizing Any Scale Or Mode On The Guitar

It’s important to state at the outset that the method I’m employing is only one possible way to approach this exploration. I’ve taken this approach to maximize the number of unique voicings, but you should feel free to take any of the rules that I’ve applied to this approach (like eliminating octaves) with a grain of salt. The object is to gain new sounds – so change the patterns here in whatever ways necessary.

.

Here’s an approach that will give you more voicings and lines than you might have thought possible.

.

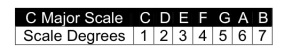

- Step 1: Write out a scale and write the scale degree under each note.

(Example: C Major)

- Step 2: On a blank chord sheet – write out the scale degrees on each string up to the 5th fret.

.

(To clarify: The numbers on the left hand side of the diagram are the fret numbers ).

.

.

- Step 3: Starting with the lowest note on the lowest string, write out all the initial voicing of all possible 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 note harmonies by scale degree on different string sets.

.

For example, if I was looking at the G, B and high E strings, some sample initial voicings would be

573, 574, 576, 513, 514, 516, 523, 524, 526, 534, 536

673, 674, 675, 613, 623

713, 723

173, 174, 175, 176, 123

.

You may have noticed that I skipped some voicings:

.

If you want to save some time and increase the number of unique chords try the following parameters:

.

- No doubling of chord tones (Ex. 363). (Again – if you like that sound – use it! but the point of this process is to generate unique voicings with unique notes.)

- At least one note in the voicing has to be the lowest on a string. If you look at 614 on the G, B and high E strings you’ll see that it’s really the second voicing of 573 on the frets below it. Having at least one note be the bottom note on any string will help ensure that you’re not just working out voicings that you may have already done.

- The highest fret to be used in the first voicing is the 5th fret. This last step is going to produce some voicings that aren’t playable on the lower frets, but might work in the upper registers.

.

- Step 4: Select a string set and move the voicing in scale-wise motion up the strings to the octave.

.

For the purposes of this lesson – I’m going to focus primarily on 3 string groups, but this idea is applicable on any 2-6 string set of strings. (It’s worth mentioning that – Harmonic Combinatorics does all the work for this process for all string sets – (it’s also why it’s over 400 pages long!!)).

.

.

(Again, while this book follows this process through the key of C Major, this process can be applied to any tonal center.)

.

- I’ve written out an example based on the D, G and B string set (i.e. 432) and gone with an initial voicing of a F, G and D (or 452).

.

(Note: The reason I start with numbers instead of notes is 1. It’s a lot easier to see if I’ve missed a number in a sequence when working these things out and 2. It eliminates the initial step of wondering what harmony I’m creating. This is simply a process that I’ve used with good results. If the numbering is weird for you, just use what works for you.)

.

.

.

- This creates seven different voicings which could be played as a modal chord progression, used as the basis for a melodic idea or even isolated into individual chords. If this process yields even one chord that you like it’s worthwhile.

.

- The function of the voicings will depend on the root. If you want to dig deeper into this area, you can use other notes as a root (note Harmonic Combinatorics includes a chart which shows all chord tones based on scale degree). I’ve posted the sound of the chords being played against an A root below. A was picked as a root because it’s an open string, but you could just as easily tap any note from the C major scale to create various modal sounds:

.

- Playing C as the bass note will give you C Ionian sounds

- Playing D as the bass note will give you D Dorian sounds

- Playing E as the bass note will give you E Phrygian sounds

- Playing F as the bass note will give you F Lydian sounds

- Playing G as the bass note will give you G Mixolydian sounds

- Playing A as the bass note will give you A Aeolian sounds

- Playing B as the bass note will give you B Locrian sounds

.

Check out these chord sounds over A. In addition to possible comping ideas, these can be arpeggiated for melodic ideas as well.

.

.

A few notes on working with voicings

.

Here are some additional points to consider when using this process:

.

- Common sense is your friend. If a chord seems difficult to play:

.

there is almost always an easier way to play it on another string set.

.

.

Since the voicings presented are in the key of C Major with no sharps or flats, the information (and approach) here is easily adaptable to other scales, modes etc…

.

- If you find a voicing in C Major you like, just move it to whatever other key you’re playing in.

- To create all of the C Melodic Minor (i.e. Jazz Minor) voicings – just change any E to Eb.

- To create all of the C Harmonic Minor voicings – just change any E to Eb and any A to Ab.

.

Now I’ll talk about making melodic lines from this material.

.

Melodic Variations

.

As I mentioned earlier, these voicings can be played as melodies simply by playing the notes one at a time. In The GuitArchitect’s Positional Exploration and the GuitArchitect’s Guide to Modes: Melodic Patterns, I’ve outlined a series of methods for generating melodic variations. But since this approach is about combining things, it makes sense to at least look at some melodic possibilities with regards to note choice. I’ve decided to take a three-note voicing as it offers enough possibilites to be interesting, but not too many to be over-whelming and have chosen this pattern simply because I like the first voicing.

.

.

It sounds a little deceptive if you play it as is. This is because the first voicing is actually a G major chord in 1st inversion (i.e. with B in the bass). Here it is with the root of each chord added to the low E string (Try working them out and playing them!! There are come challenging chords there.)

.

.

but when you play it with the B as the lowest note it sounds like a B minor with the b3rd on the B string.

.

.

If you play it without harmonic backing, try changing any F natural to F # and it should sound more pleasing to you.

.

“Variety is the spice of life”

.

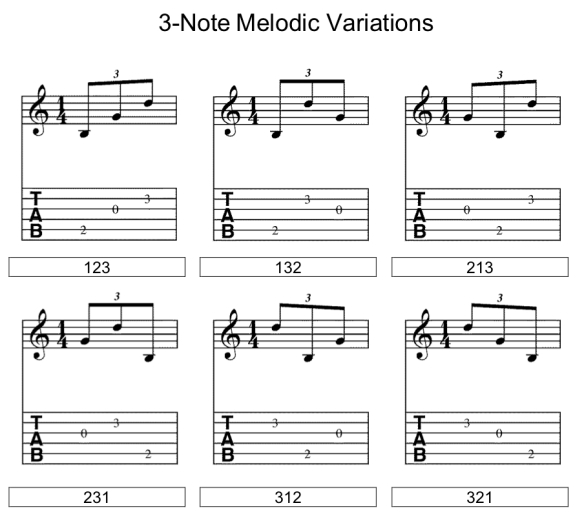

There are six unique melodic variations of any three-note chord or pattern.

.

.

These numbers represent note order. Assigning 1 as the lowest note and 3 as the highest – here are the unique variations on the first three notes.

.

Applying this idea, one possibility for 123 looks like this:

.

.

.

Two things to consider:

.

1. I’ve notated this as triplets for ease of reading, but the very first thing you should probably do (after getting the notes under your fingers is look for a more musical phrasing).

.

.

2. Again, if you play this without harmonic backing this may sound more “right” to you:

.

.

Alternating groups of 123 and 321 for each chord produces:

.

.

.

Combining the first 2 chords into a 6-note pattern allows even more flexibility. Here, I’ve moved the number order around and made a more interesting line.

.

.

.

One part of this phrase has caught my ear:

.

.

When I add a low E root, I get a cool little Phrygian phrase (with a couple of notes snuck in on the high E string).

.

.

The GuitArchitect’s Positional Exploration and the GuitArchitect’s Guide to Modes: Melodic Patterns, has a systematic approach to exploring these types of variations. Having said that, those of you who want to do the work, could just write down a collection of numbers and apply them to different ideas and see what happens.

.

The first important thing, however, is to experiment with different rhythms (including rests!), phrasings (like slides, hammer-on/pull offs) and make some music out this raw material.

.

The second important thing to consider is that with any approach like this you should:

- take the things you like

- use them in what you’re currently working on (songs, solos, etc)

- make what you keep part of your sound and discard (or ignore) what you don’t use.

.

I cover some other approaches and break down the theory a little more in depth in Harmonic Combinatorics but I hope this lesson here helps and if you like this idea – you should check out the book (if you haven’t already)!

.

Thanks for reading!

.

-SC

.

If you like this post you may also like:

in the following statement I do not see the 573 as being the seconfd voicing. The 6 on the G string is one fret higher in relation to the 1 & 4 wheres the 5 is right above the 7 & 3! Please explain further

■At least one note in the voicing has to be the lowest on a string. If you look at 614 on the G, B and high E strings you’ll see that it’s really the second voicing of 573 on the frets below it. Having at least one note be the bottom note on any string will help ensure that you’re not just working out voicings that you may have already done.

Hi Todd,

Thanks for posting. The statement refers only to the process of generating voicings.

What I’m saying is that if you’re moving a set of voices up a scale one note at a time, that 614 is the 2nd voicing of 573.

Case in point:

573 on the G, B, and E strings are notes (Low to high)

G-B-E

Now going through the process I describe of moving each note up the C major scale on each string I’ll get the following notes:

GBE (open strings -(573)

ACF (614)

BDG

CEA

DFB

EGC

FAD

GBE (12 fret voicing)

So if I start working out patterns from 614 (ACF) in the same manner – I’m going to produce the same sequence of chord voicings as if I start from GBE. Any voicing here is fair game, but the “rules” I’ve posted are just a way to make sure that (if you’re working systematically) that you’re not working out anything that you’ve already done.

Again, it’s just a suggestion for efficiency in working through these things – but as with anything, take what sounds good to you and use it!

I hope that helps!

If you have other questions – just let me know!

Thanks again

-Scott

Wow, this is a whole new world! Thanks for the insights, I have lots of homework to do – even more than I originally thought! Kudos…

Thanks Mal – I’m glad you enjoyed it.

If you want to save some time – you can pick up the harmonic combinatorics book. In addition to a number of other approaches (and more more in depth breakdown and analysis) – it also has all of the 2-6 string variants mapped out!!!! (that’s also why it’s 410 pages!)

It might seem like a lot but it’s really a instructional and reference book. Something to pick up grab an aidea of out and explore until you need another one.

Good luck with the approach!

-Scott

Hi Scott,

Interesting stuff. I bought the 3 pdf bundle. It was an easy decision for $30. I thought the theory might be a bit above me or not suit my style of playing but they’re very well written and laid out. I’m going to work my way through them slowly and digest it in small chunks, there is a lot of it.

What order would suggest going through the books to get the best from them.

Hey Gary,

Thanks for the comment (and for the bundle order!)

As I’ve mentioned in the practicing posts – one really important factor in practicing is consistency.

A commonality with the books is that they’re all centered around one approach or idea and then thousands of variations on that idea. So once you get familiar with the concept behind each book, all you really need to do is pick an idea and explore it it. The books are all modular so it doesn’t really matter which one you start with.

That being said: here’s a sample approach.

Day 1: Take a 1/2 hour (or more if you get engaged in it!) and read the intro to harmonic combinatorics. Then pick one 3-4 note combination and then follow the suggestions in the how to use this book section. Try to write a song with the idea, work one of the voicings into a song you already know or use it as a springboard for a melodic idea.

Day 2; Take 10 minutes to work on the ideas that you developed yesterday (or pick a new 3-4 note voicing to work on) and then follow the instructions form day 1 either with the same book or with a different text. Melodic Patterns might be a good one move onto.

The goal is to get to the point that you understand the ideas behind the books and then just pick a pattern, chord or voicing a day and work on it for as long as you can be engaged. That might be 10 minutes if it’s a pattern from the positional exploration book or it might be hours if it’s a 9-note pattern in Melodic Patterns or an interesting intervallic or chord idea in Harmonic Combinatorics.

Try to work a little on all three every day. Even if you only put 10 focused minutes of proper practicing in on any of the material, you’ll notice growth in your playing and your ability to sonically visualize things. It sounds like ad copy from an info-mercial, but it’s true. You’ll get out of it what you put into it.

Each book has a section about how to use the book and there are a whole series of posts on the site for how to practice. Get yourself a comfortable chair, a metronome, a timer and a practice log and you’re off and running.

If you have more specific questions just ask!

I hope this helps!

-SC