In the previous getting through the gig post, I talked about how to interpret chord symbols to determine what a song is asking for. Today, I’m going to use upper structure triads (triads built on chord tones other than the root) to simplify the chart. If you’re unfamiliar with the chord symbols below, you may want to start with Part 1 of this lesson.

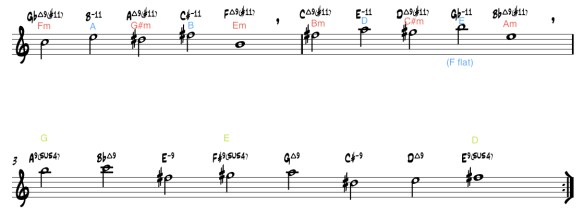

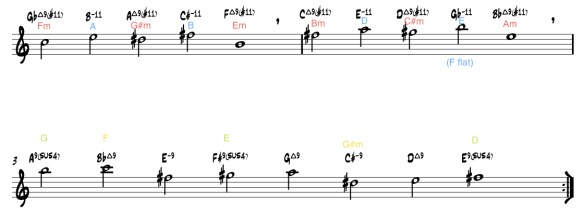

This lesson will continue to use the 232 chart used in part 1.

.

(232 © Chris Lavender 2011 used with permission)

.

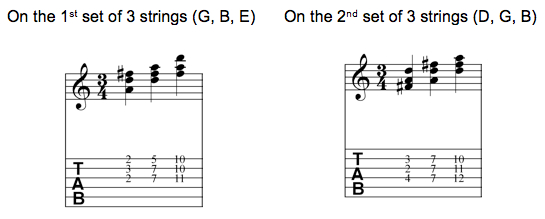

For now – let’s assume that you know how to play at least some major and minor triad shapes. (If you didn’t take my advice to review the triadic inversions at the end of the last post – you may want to do so now.)

.

Getting through the Charts part 1 – Unfamiliar and familiar

When sight-reading a chart, my goal isn’t neccessarilly to have a brilliant interpretation playing it the first time (although if I can make it better – great) . I just want to make sure that I’m playing the chords as written and then try to adapt it to the song. So if I have stock voicings at my fingers for chords on the chart and they make sense, I’ll play those and then voice lead or tailor the approach from there.

Let’s assume for a moment that it’s a worse case scenario – you’re given this chart to play and all of these chords are alien to you.

.

Step 1:

Look for common chord types.

In this case, there are only a few different types of chords in the piece:

- major9 #11

- minor 11,

- 9sus4,

- major 9 and

- minor 9.

If generic voicings can be developed they can just be moved to the roots of the chords that need to be played.

.

Step 2:

Convert to the key of C and figure out the chord formula.

The reason to convert to the key of C – is that the lack of sharps or flats in the key signature makes it easy to alter chord formulas as need be.

Here are the chords in question in the key of C:

C major9 #11: C, E, G, B, D, F# (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, #11)

C minor 11: C, Eb, G, Bb, D, F (1, b3, 5, b7, 9, 11)

C 9sus4: C, F, G, Bb, D, (1, 4, 5, b7, 9)

C major 9: C, E, G, B, D (1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

C minor 9: C, Eb, G, Bb, D (1, b3, 5, b7, 9)

.

Step 3:

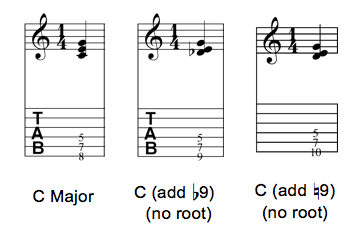

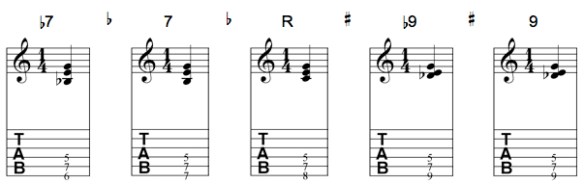

Focus on the upper notes (7, 9, 11, 13) of the voicing (and/or any alterations) and make a short cut:

Note:

This process assumes that there’s a bass player who will be playing the root. You also loose the 3rd in the voicing, but you can always add the root, 3rd or any other chord tone in later. The initial step is to just get through the chart, and then spruce it up as you gain familiarity.

In the C major9 #11, the upper notes are the 7, 9 and #11 (B, D, F# ) this is a B minor triad with a C in the bass (also written B min/C).

The shortcut here is –

if you play a minor triad a ½ step down from the root

you’ll have the upper extension of the major 9 #11 chord.

Here are the transposed voicings

Gb major 9 #11 = F minor/Gb

A major 9 #11 = G# minor/A

F major 9 #11 = E minor/F

C major 9 #11 = B minor/E

D major 9 #11 = C# minor/D

Bb major 9 #11 = A minor/Bb

Here they are penciled into the chart:

Note:

I’m going to into specific voicings in the third and final post – the idea here is to just to document how to figure out some basic chord substitutions. While I haven’t written in the bass note (i.e. Gb major 9 #11 = F minor/Gb – written on the chart as simply Fm), the bass note is still in the original chord voicing, so I can work it into the tonic as necessary.

In the C minor 11, the upper notes are the b7, 9 and 11 (Bb, D, F) this is a Bb major triad with a C in the bass (also written B/C).

.

The shortcut here is –

if you play a major triad a step down from the root

you’ll have the upper extension of the minor 11 chord.

Here are the transposed voicings:

B minor 11 = A/B

C# minor 11 = B/C#

E minor 11 = D/E

Gb minor 11 = Fb(E)/Gb

and applied to the chart:

Next, let’s look at the 9 sus4 chord

C 9sus4: C, F, G, Bb, D, (1, 4, 5, b7, 9)

Here the upper extensions are the b7, 9 and the added sus4 (Bb, D, F)

The real difference between the C9 Sus4 and the C minor 11 is the Eb.

.

The shortcut here is –

if you play a major triad a step down from the root

you’ll also have the primary tones of the 9sus4 chord.

Here are the transposed voicings:

A9 sus 4 = G/A

F#9 sus 4 = E/F#

E9 sus 4 = D/E

and applied to the chart:

For 11 and 13th chords, I tend to think in terms of triads based on the 7th or the 9th. Major and Minor 9th chords can be seen as triads starting from the 5th (but I usually see them as 7th chords from the 3rd – more on that in part 3 of these posts).

Major 9th shortcut –

if you play a major triad chord a 5th up from the root

you’ll have the upper extension of the major 9th chord.

Here are the transposed voicings:

C major 9: C, E, G, B, D (1, 3, 5, 7, 9) = G/C

Bb major 9 = F/Bb

G major 9 = D/G

D major 9 = A/D

and applied to the chart:

Minor 9th shortcut –

if you play a minor triad a 5th up from the root

you’ll have the upper extension of the minor 9th chord.

Here are the transposed voicings:

C minor 9: C, Eb, G, Bb, D (1, b3, 5, b7, 9) = G Minor

Emin9 = B min/E

C#min9 = G# min/ C#

And the big reveal or…

GET ON WITH IT ALREADY SCOTT – WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?

Okay here’s the initial chart again:

.

and here’s the modified chart with triadic substitutions written in (click on the chart to see it full-sized).

.

.

Which do you find easier to read chord-wise?

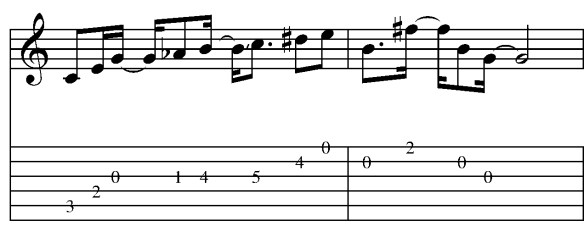

“Hey take a solo…”

As an additional bonus to this approach, these upper extension triads can also be approached as arpeggios that can be played over each chord for soloing or as a simpler tonal center for chord scales (just realize that not all chord scales that work for the upper extension triad will work for the initial chord – but experiment and use your ear to guide you for what works.)

In the final post of this series, I’ll show how I ended up voicing the tune.

Thanks for reading!

-SC