I took the wrong weekend to sleep in! Guitar Squid distributed a link to part one of the post and by the time I got to check my stats for the weekend I had already missed my record keeping days.

However, you got here – welcome.

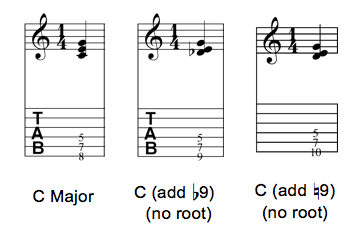

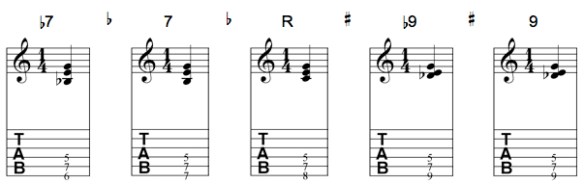

In the previous posts (part 1 and part 2), I talked about deciphering chord symbols and developing shortcuts for playing them. In this post I’m going to talk about my approach and how I ended up reading the chart.

.

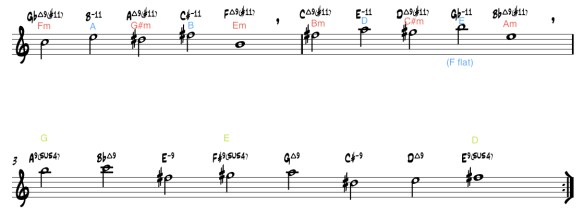

One final time – here’s the 232 chart with upper extension triads written in:

.

Here’s an mp3 of the track. This was recorded with an FnH Ultrasonic recorded directly into AU Lab with PodFarm 2.0 @ 44.1. The goal was an ambient wash of sound but in retrospect, I should have gone with a longer delay time/wetter reverb to hold the sustain.

Here’s the PodFarm Patch:

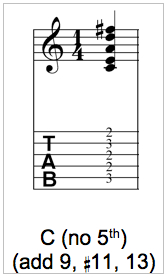

Here’s Bar 1 of the chart:

Notes:

- Simple is better. I usually start with 3-4 note voicings and then add from there on subsequent passes.

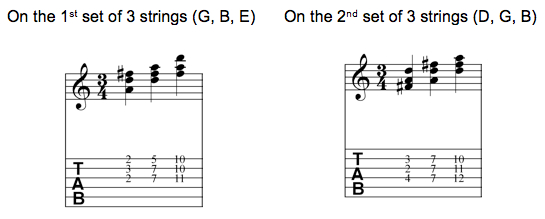

- I chose the F minor chord in the first position to make the C in the chart the top note of the voicing (and thus accent the melody) – this kept my initial focus on voicings primarily on the D, G and B strings.

- I added the bass note on the E and A strings so I could get a little more of the chord texture.

- On the B minor 11 chord, I made some alterations on the fly. To get the melody note on top of the voicing I doubled the 11 (E on the 5th fret). Technically this isn’t a minor 11 chord as there’s no 3rd – but in this case Chris was playing the full voicing anyway, so I’m just adding texture. Depending on what the bass was doing on the second pass I would probably add the 3rd of the chord (D) on the 5th fret of the A string.

- The 3rd and 4th chords follow a similar pattern so I used the same voicing.

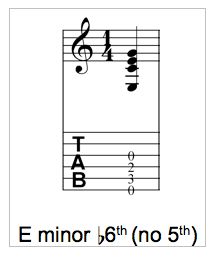

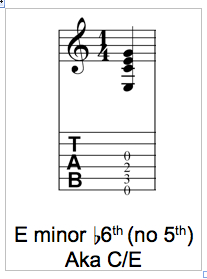

- I decided to drop down to 1st position for the last chord to get some low-end emphasis. I’d probably add some harp harmonics as well.

- The same voicings and approach are used in Bar 2.

.

Bar 2

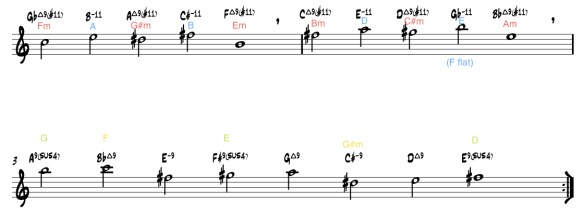

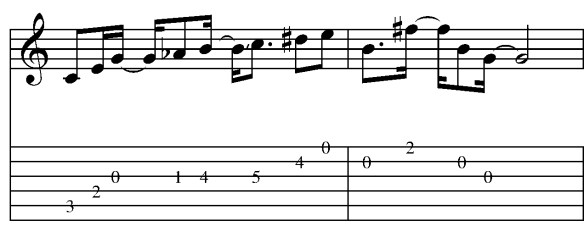

Bars 3-4

Notes:

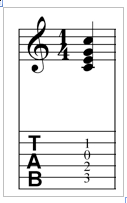

- A 9 (sus4) – This went to g,b and e strings to facilitate the melody note. With the kind of ambient swell sounds that I used – muting the strings with the pick hand between chord changes becomes important to maintain smooth delay.

- Bb Maj 9 – Here I was actually thinking Dm 7/Bb. So I’m just using the top notes of the voicing.

- E min 9 – This is a stock A string minor 9 voicing I use. I have a couple of these for E and A strings I throw in when I need to.

- F#9 (sus 4) – E maj/F# voicing based off of a VII position E barre chord.

- G maj 9 – I was thinking B min but then added the A on the 10th fret for the melody and the G on the A string for the root.

- C#min 9 – I moved the melody up an octave on the last 3 chords to amp up the arrangement. Stock E string rooted voicing. Sometimes I’d play the B on the D string and sometimes not.

- D Maj 9 – Variation on the C#min9 shape – 2 useful voicings to have at your disposal.

- E9 sus 4 – Just kept the D Maj 9 voicing, added the F# on the top string and played the low octave E. I addition to filling out the chord the voicing puts me in a good spot space wise if we decide to repeat bars 1-4.

.

This has been a long series of instruction for a pretty simple chord chart, but the purpose of it was to detail the process behind those short cuts. It might seem long and involved – but it gets easier over time. In reality – the voicings took about a minute to suss out.

.

I hope this helps! Please feel free to reply here or send an email to guitar.blueprint@gmail.com with any other questions you might have about this.

-SC