Hello everyone, and welcome to the largest GuitArchitecture lesson I’ve ever put up online!

.

In this lesson (an excerpt of some ideas from my forthcoming GuitArchitect’s Guide to Modes book), I’m going to talk about the difference between scales and music and show some concrete ways to adapt scales into unique phrases.

.

When I first started playing guitar, I listened to a lot of metal and the players I was into were fond of working ascending and descending scales into their solos. (I also listened to a lot of Al DiMeola on Friday Night in San Francisco as well). So I initially focused a great deal on scales and got to the point where I could play them quickly (but not really cleanly). The flash of this got me noticed by other players in my area, but I always felt like something was missing.

.

At best, scales are only ½ of the equation

.

Seeing where my fingers needed to go was important but phrasing is where the real music is happening.

.

Note:

There’s a lot of information below. Just take your time and go at your own pace. It’ll still be there later.

.

Here’s another way to think of it. Scales are like basic vocabulary. They’re your nouns and verbs and no matter how you speak (with arpeggios, intervals or chords), they all have a basis in scales.

Your phrases are your sentences. Guys with great phrasing can play a scale and make sentence out of it. But a scale is, in and of itself, largely just a tool in making music and not music itself.

.

First Steps: Music is a language.

So approach it the way you approach your native language

.

The way we learn language is by listening to other people speak and then emulating their speech. Initially it’s nonsensical. Then some disjointed vocabulary emerges which eventually gives way to sentences. There is typically a period of formal study where reading is taught, and students are required to write ideas down. Eventually, we take on unique characteristics that make our voices distinct. With daily exposure language, and our understanding of it is constantly evolving.

Learning music is the same thing. It first requires active listening. You need to find music that you’re passionate about and really work on learning it by ear. Music theory is also important, because it can help you make shortcuts to understanding a sound (for example, “that Phrygian pattern” gives the informed listener an idea of what a sound is before he or she even hears it), but really getting into phrasing requires an aural understanding. Initially, this will take a long time and you probably won’t have all of the technical skills that you’ll need to get it at 100% accuracy. That’s fine. Get what you can – but really pay attention to phrasing details like pitch (vibrato, slides, bends, etc) and rhythm. If at all possible – try to sing along with what you’re trying to learn. If you get to the point that you’re not enjoying it – move on and come back to it. The more you actively enjoy what you’re doing, then more you will get out of it.

.

Step 2 involves listening out of your comfort zone.

.

Try checking out music from other (non-guitar playing) musicians and cultures as well. A lot of my pointillist rhythm ideas were copped directly from Japanese Koto approaches. I stole a lot of things from Arabic music (specifically Turkish folk and classical music, the Iranian Radif and various maqams), Hindustani music, and vocal music from around the world. I copped gypsy violin and accordion licks and Klezmer clarinet lines. Lately I’ve been super into the insanely wide vibrato and pitch bends in Vietnamese Dan Bau music. The important thing is searching out for other sounds, getting inspired by them and taking something from them.

For me a lot of this has been the nonsense portion of trying to speak other musical languages. Not everything I do translates in multiple musical situations. It’s not always correct or accurate, and sometimes that’s even better because then it’s my own spin on it.

Really importantly – not all of it sticks. I spent a lot of time learning things that didn’t directly work its way into my playing. That’s fine. The important things are the things that will ultimately stick with you. What it’s given me are some things that are distinctly mine now. A distinct accent if you will, that immediately identifies a handful of things that I say as me.

.

Next Steps:

.

In addition to learning things by ear, having a few different approaches to using scales in your bag can help give you the flexibility to express some really musical things. I’ve already posted on the area of limiting options, and with that in mind I think it’s more important to go deep with a few ideas, rather than just scatter-shot a number of approaches and deal with them all superficially. So I’ll cover some of them here

.

Starting point: The Scale

.

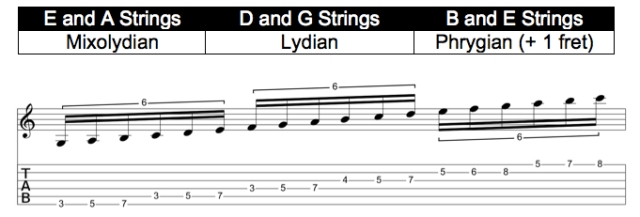

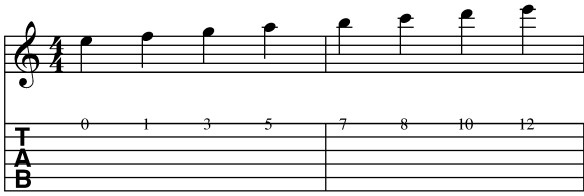

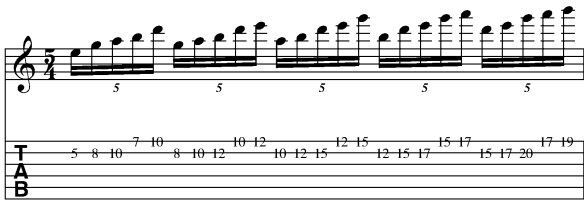

For an initial starting point, I’m going to look at a 3-note-per-string C Aeolian scale. Try running this scale a few times with the fingering and picking patterns I’ve provided to make sure it’s under your fingers.

.

.

.

In the mp3 above, I’ve played the scale in 16th’s, a C minor 7 chord (to hear a harmonic context) and then as sextuplets.

.

Note:

In some textbooks you’ll see the b6 as an avoid tone against a minor 7 chord (i.e. the Ab as an avoid tone for C minor 7). You can always just play a minor triad or a 5th for a similar effect. I’ve included the minor 7th here because – aesthetically – it doesn’t bother me and I like the sound of a minor 7th better than the triad.

.

Picking this as I have above results in a smoother (almost legato) sound than I could get using alternate picking, even though I’m still picking every note. For the initial fingering, I’m playing the first 2 notes of each grouping with my 1st and 2nd fingers to facilitate the slight positional shift on the B and E strings.

.

Note: When practicing any musical idea, it helps to have a melodic and rhythmic context. A time keeping device can certainly help, but I’ve included a short C note for a drone and a drum loop for your convenience below:

.

.

.

Approach #1: Skipping notes and using patterns

.

The only time I use straight ascending/descending scales is if I have a target note that I’m specifically trying to get to. In those cases, having some velocity to get there can build tension and make it exciting to hear. Otherwise when you hear one note after another in straight ascending or descending scalar patters, it gets very predictable pretty quickly.

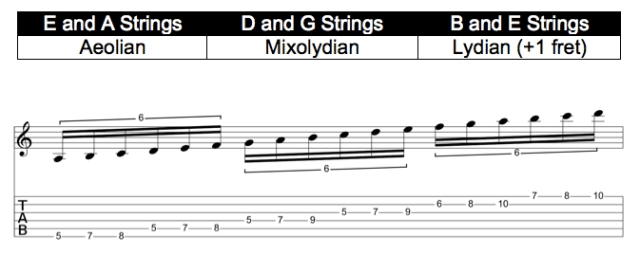

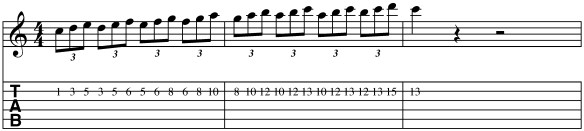

Here’s a sample phrase I improvised based on the scale above. I’ve added some notes below.

.

.

.

- On the first part of the phrase on the A and G strings, I’m only playing the notes C, D and Eb. Adding a string skip and doubling the C at the octave creates more excitement in the phrase. I’ve provided an optional notation indicating picking the octave C with the pick hand middle finger to give it a little snap – but you can certainly flatpick it as well.

- Starting on the Bb on the G string, I’ve rhythmically copied the same phrase as on the A and G strings. By playing it as a pattern, it creates some consistency in the phrase. While the rhythm is sextuplets – the phrasing is alternating groups of 4 and 6.

- The last 6 notes break out of the pattern by just playing a straight ascending scale.

..

Here’s another track variation. I’m picking every note on this one:

.

.

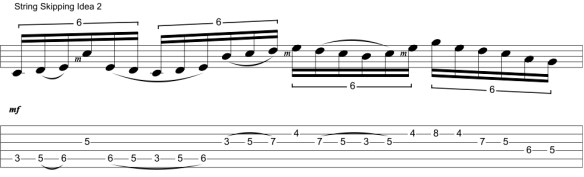

Approach #1a: Skipping notes part 2 (Pentatonics)

.

Another way to work scalar ideas into a musical context is to reduce scales to pentatonics. For example: Here is my initial scale again:

.

.

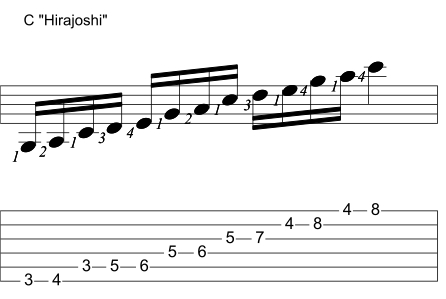

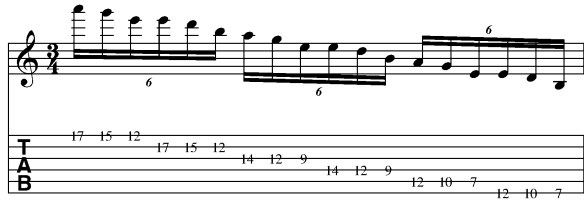

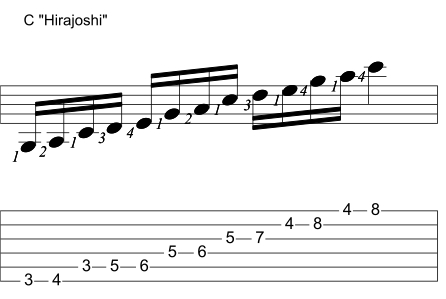

And now I’m going to remove the F and the Bb from the scale. This leaves a five-note pentatonic (C, D, Eb, G, Ab) – sometimes called Hirajoshi.

.

.

.

The term, “Hirajoshi”, actually refers to a Koto tuning. In the Japanese scale system, this collection of intervals would be recognized as belonging to the In scale. But since so many guitarists refer to this as Hirajoshi, I’ll use that nomenclature here.

Regardless of what you call it, sonically it’s a very cool scale. The skips between the Eb/G and Ab/C really open the scale up sonically.

.

Here’s a variation on the lick above using this pentatonic idea in the second ½ of the phrase.

.

.

.

Technically, in addition to some of the challenges of the first lick, another tricky thing here is the skip from the C to the Eb on the G and B strings because the D, C, Bb pull off wants to go back up to D. Sonically though it adds a really nice contour to the phrase.

.

Approach #2: Sequences

.

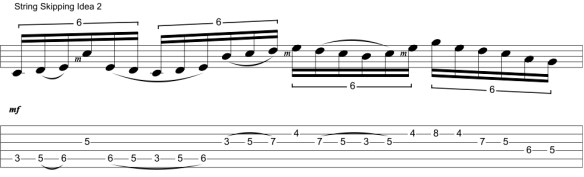

Sequences are a cool way to use scales in a way that generate melodic momentum but contain an internal logic. Here’s an example of using the pentatonic in descending groups of 3s.

.

.

.

This is a very Marty Friedman-esque idea. A little goes a long ways with this type of approach, but these sequences are great devices to work into phrases as a way to get more mileage out of a scale.

. .

Approach #3: Octave displacement

.

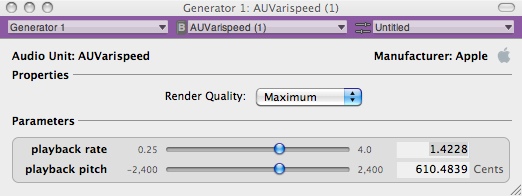

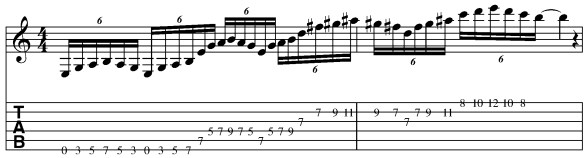

Playing notes in order can be boring, but as we saw with the octave C jump in the first lick, alternating scale notes in different registers can be much more interesting melodically. Since the A and B string are a 9th apart, playing an ascending melody between the strings works well positionally.

The first step in this process involves being able to visualize the scale on each individual string:

.

.

Here’s a melodic idea that works off of this ascending/descending idea. It works without a trem as well, but adding the trem gives it more of a slidish feel. The important thing is to let it all ring together in a controlled way. I’ve recorded this at full tempo and then in 1/2 time and I think it works a lot better at 1/2 speed .

.

.

.

If you look at the notes in the phrases (C, D, Eb), (D, Eb, G), (Ab, Bb, Ab), (G, F, Eb). They’re all based on short simple melodic ideas that sound more complex when broken up over octaves.

.

Approach #4: Modal Arpeggios

.

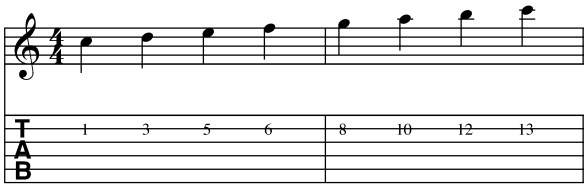

Previously, I removed two notes to create a pentatonic scale but if I play every other note of a mode, I can create an extended arpeggio called a modal arpeggio.

For example, here’s the scale again:

.

.

Taking every other note:

.

.

And putting it into a phase gives me this:

.

.

.

Note#1:

It’s interesting because while the scale and tonality is rooted in C, sliding the last note of the arpeggio up to D gave it a whole other texture.

.

Note #2:

A lot of phrasing is really about minute details. Here’s the same arpeggio but I sit on the first note just a little longer. It makes the phrase more musical to me:

.

.

Here’s another arpeggio idea with a repeated phrase in the middle.

.

.

.

.

Playing arpeggios on smaller string sets allows me to sequence ideas more easily (Like the first 5 notes). The jump to the Eb is probably the biggest surprise in the phrase. Short but sweet.

This modal arpeggio approach can be applied to any mode or scale and offers a great way to add some additional textures into your soloing.

.

Some Concluding Thoughts

.

Normally, I would have broken this up into multiple posts, but I though it was important to get the aural learning component and the melodic variations on the same page.I didn’t even get into rhythmic variations, double stops, chromatics, chordal applications, superimpositions or any of the literally dozens of other approaches that can be used to extract music from scales. It really all comes back to how much music you’ve absorbed because the most used tools in your melodic toolbelt are going to be your ears and your aesthetic and those are both guided by what you’ve been exposed to.

For those of you using GuitarPro, you can download the .gpx file of this lesson (with an extra arpeggio thrown in for good measure) here.

.

The GuitArchitect’s Guide To Chord Scales

.

I’ve mentioned before, that (for me) the biggest advantage of investigating harmony and theory is to expose people to sounds that they didn’t know where there. This is the entire purpose behind the GuitArchitecture series. One of the GuitArchitecture books in that series, The GuitArchitect’s Guide To Chord Scales utilizes and expands on this idea by exploring all unique scales from 3-12 notes!!! The above material is expanded on substantially in that book so if you like this lessons you’ll really like the book.

More info on the book here.

Lulu Link

Amazon link

If you like this book you might want to check out the other books in this series here.

As always, thanks for reading!

.

-SC