In Part 1 of this lesson, I went over how to create a chord scale for improvising over a specific chord (in this case C major) chord. As a brief recap – here is the chord scale I chose:

.

C major chord scale with a # 2, # 4, and a b6 scale degree.

.

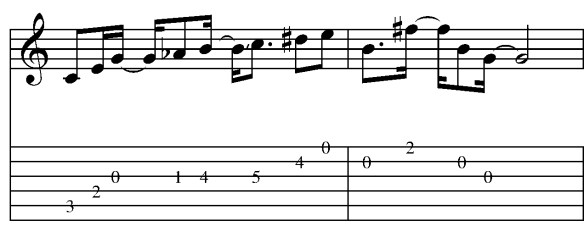

To start this off – here’s a sample lick using this scale:

.

Here’s how the scale sounds played slowly (1/4 note at 90)

Here’s the scale faster (1/4 note at 180).

.

The chords you say?

Since we’ve engineered this chord scale around a C major triad – we know that any licks we come up with will work over that chord – but to see what other chords can be used with this scale – we need to harmonize it.

Let’s look at the triadic (3 note) harmony first.

.

C major chord scale with a # 2, # 4, and b6 scale harmonized in 3rds (triads)

.

**Note the first 2 chords have been moved to the back three strings to facilitate playing:

.

Here are the chord formulas that are generated:

- C, E, G – Root, 3rd and 5th – C Major

- D#, F#, Ab – Root, 3rd and double flat 5th – non functional harmony*

- E, G, B – Root, flat 3rd and 5th – E minor

- F#, Ab, C – Root, double flat 3rd, flat 5th – non functional harmony*

- G, B, D# – Root, 3rd, sharp 5th – G Augmented

- Ab, C, E – Root, 3rd, sharp 5th – Ab Augmented

- B, D#, F#, – Root, 3rd, 5th – B Major

(Note: even though these don’t have a triadic function they can serve a function enharmonically – I’ll get to that in the 7th chord section).

To recap – any licks that we generate from this scale will work over C major, E minor and B major.

.

Adding the spice

Since we started this approach with C major – let’s look at a lick that spices up a C Major Triad.

.

Here’s an mp3 of the lick. This is an example of something I might play as a backup accompaniment in the pre-chorus of a song.

To my ears even playing this over a straight C major tonality, the D#–>E really triggers an E minor tonality. Try playing this over a C major –> E minor progression.

.

Moving to E minor – here’s an approach I use a lot in rhythm playing.

.

The first step is to take a set of three strings – in this case I’ll use the high E, B and G strings.

Starting with a sample chord voicing in the low register – ascend up the neck by moving each note in the voicing up by scale degree. In this example:

.

I’ve started with an initial voicing (Ab, C and E) and moved it through scale-wise motion.

.

(Note: I hear this as G# instead of Ab – you may want to see the section on enharmonics below).

.

Here is an mp3 of the voicings. In the audio example, I play a low E between each chord to establish an overall tonality.

Having done this – I see some cool dyads ( 2 note voicings) on the B and G strings that I can use to spice up an E minor vamp. This is an example of the type of comping I might do on the verse of a song if the song chart just said E minor).

.

Here is an mp3 of the lick. Don’t be afraid to lay into the slides or add a little vibrato to make the notes sing a little more.

With a lot of these approaches – I’m not really conscious of what the specific functions of the notes are. Once I know that the scale will work over a chord – it’s more about focusing on the sound of the notes and how they fit into the song. On some tunes – these notes would clash with the melody and it wouldn’t work.

This process is about building a repertoire of sounds to have at your disposal. Knowing the theory around it just allows you to adapt those sounds and approaches to make the fit where you want them to.

.

Space is the place

Here’s a lick that takes the above approach of breaking chords up into different string sets and applies it to a melody line. Here I’ve focused on the A, D and B strings and added in the high E string at the end.

.

Here is an mp3 of the lick. Note the slides, vibrato and slightly rubato phrasing at the end of the lick. These are the little nuances that help make the difference between playing music and playing notes.

This next lick combines chord forms and melody by using artificial (i.e. “harp”) harmonics. To produce these – a chord shape is held with the fretting hand while the picking hand picks and partially frets notes 12 frets higher resulting in a chime like timbre. If you are unfamiliar with this technique – just google Lenny Breau (an absolute master of the approach) and you’ll get an idea.

For this specific lick: I’m holding the D# with my second finger, the C with my 3rd and the Ab with my 4th so I can reach the F# with the fret hand 1st finger.

.

Here’s an mp3.

.

One of the secrets of this method is to strategically time the release of the fret hand notes. The longer you can leave the notes held down, the more the pitches will bleed into one another – which produces the desired effect. Before we go to the next lick I need to make a brief enharmonic diversion.

.

An Enharmonic Diversion

An enharmonic is when a note is spelled differently but sounds the same (for example Ab and G#). When playing this over an E drone – I hear the pitch on the first fret of the G string as a G# (i.e the third of the chord) instead of Ab. It’s very difficult for me to hear that note functioning as a b4.

As a case in point, here’s another lick. (This piece makes liberal use of vibrato bar scoops – listening to the mp3 of the lick for phrasing is recommended).

.

.

I’ve notated this lick with both a G# and a G natural as those are the intervals I hear in the approach.

With this interpretation it makes the scale harmonically vague as it would then have both a major AND a minor 3rd. If we go back over the initial triadic chord and replace the Ab with G#, F# for Gb and D# for Eb we get a couple of different chord options.

- C, E, G#- C Augmented

- E, G#, B – E Major

- G#, B, D# – G# minor

- C, Eb , G – C Minor

- G, B, Eb – Eb Augmented

- Ab, C, Eb – Ab Major

To recap – in addition to C major, E minor and B major – these licks can also be used with care over E major, Ab major, C minor and G# minor.

.

To finish this approach out for now – let’s look at 7th chords.

.

C major chord scale with a # 2, # 4, and b6 scale harmonized in 3rds (7th chords)

**Note: the stretch on the second chord should be approached with caution. If it hurts – stop playing immediately!

.

Here are the chord formulas that are generated:

- C, E, G, B – Root, 3rd, 5th and 7th – C Major 7

- D#, F#, Ab, C – Root, 3rd and double flat 5th, double flat 7 – Enharmonically – this spells – Ab, C, Eb, Gb, – or Ab7 – but doesn’t serve a function from the D# pitch.

- E, G, B, D# – Root, flat 3rd, 5th and 7th – E minor (Major 7)

- F#, Ab, C, E – Root, double flat 3rd, flat 5th – Enharmonically – this spells – Ab, C, Eb, Gb, – or Ab7 – but doesn’t serve a function from the F# pitch.

- G, B, D#, F# – Root, 3rd, sharp 5th, 7th – G Augmented 7

- Ab, C, E, G – Root, 3rd, sharp 5th – Ab Augmented 7

- B, D#, F#,A – Root, 3rd, 5th, flat 7th – B7

This gives us a couple of new tonalities to explore – namely, C Major 7th, E minor (major 7th), B7 and Ab7.

..

The final tally:

At a minimum, this chord scale will generate licks that can be used over the following chords:

C major, C Major 7th,

C minor, C minor (major 7th)

E major, E Major 7

E minor, E minor (major 7th),

Ab major, Ab7

G# minor

B major, B7

.

Next steps:

You will probably not like the use of this scale with all of the chords listed but, as is the case with any musical approach, the key is always to use your ears as a guide to what works and what doesn’t.

I hope this helps!

Happy Holidays and thanks for reading!

.

The material in the lesson is adapted from the material in The GuitArchitect’s Guide To Chord Scales book. More information about that book (including an overview and jpegs of sample pages) can be found here.

.

-SC

.

PS – If you like this post you may also like:

.