In part one of this post, I looked at generating different major chord variations based on flatting the root and the 5th. In this post, I’m looking at sharping those pitches and combining the two for additional textures (if you came here directly – you may want to review the A major variations in part one before continuing).

.

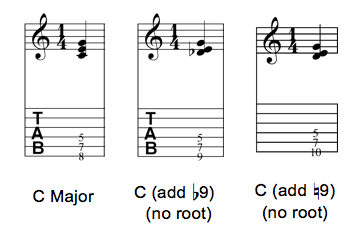

Start with a map:

Adapting chord forms requires the ability to visualize chord tones around the shape you’re using. As a starting point, here’s a fretboard diagram of an A major chord (with the A being on the 7th fret of the D string). I’ve added some additional chordal extensions on the E and B strings (but this process could be applied to any string-set).

In the last lesson, I looked at creating sounds with the 6th (or 13 – see post 1 for the difference between the 2) on the E string. This time, I’ll add the 6th (6th or 13th) on the B string by raising the E up to F#.

.

Here is the sound of the A Major 6th (no 5th) chord.

.

Comparing this to the A major 6th voicing in part 1:

.

.

The new voicing is certainly easier. If I was really stuck on the close voicing of the E and the F# in the A major 6th, I could simply move the F# to the B string and move the E to the open string like this:

.

Several Notes:

- This voicing wasn’t included in the first lesson as I wanted to show the process of how to derive these chords.

- The upside to this approach is it makes this specific voicing easier to play – but the downside is it’s not movable – which may or may not be problematic for you.

- If a chord is really difficult to finger – there is always an easier way. You may not get the specific notes or voicings you’re looking for – but there’s always an easier way.

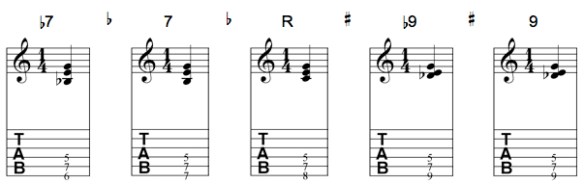

Now I’ll extend the initial Major 6th sound by flatting the 7th. This is done by lowering the A to G#.

.

Again, I’m a sucker for chords with seconds in the voicing (in this case the F# and G#). It adds a little but of tension and elevates the chord a bit.

.

Adding in the 9th:

First let’s create an A major add 9 chord.

.

.

Note:

The reason this is an add 9 chord and not a major 9 chord is the lack of a 7th.

Since the chord is a major chord with a 9th added, it’s called an add 9.

.

Now I’ll add a sharp #11. This is done by lowering the E to D#.

.

.

Another Note:

The further you extend the harmony and remove initial chord tones, the more vague the sound of the chord is as related to the tonic.

For example: The chord above could be analyzed as an A major 9 # 11 with no 7th and no 5th. But the notes are A, C#, D# and B. If those tones are centered around B – you have a B, D#, A and C# or a B dominant 9 (no 5th)/A.

If you have to analyze a chord with more than 1 elimination (i.e. “no 7th no 5th”) there’s probably a simpler analysis of the chord.

Going Further:

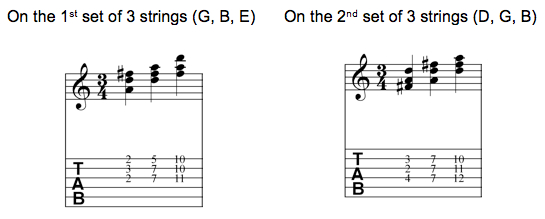

Now that some initial options have been explored – I’ll take a look at the upper notes of the voicing. If I take the previous fretboard diagram and extend a note on the G string I’ll have something that looks like the diagram below (again the A listed below is on the 7th fret of the D string):

If I’m willing to be a little adventurous and replace the 3rd of the chord (C#) with the #11 (D#) , I’ll get a voicing with a root and then all upper tensions (9, #11 and 13). Here it is notated:

.

.

While you could analyse this related to the key of A Major (A major 13, #11, no 3rd, no 5th, no 7th) you may have noticed that shape is the upper chord voicing for a VII position B 7 barre chord.

.

Short cut 1:

Playing a dominant 7th chord on the second scale degree of a major chord will get you all of the upper extensions and the root).

(i.e. B7 over A major)

But isn’t a stable sound on its own. If you play this chord and then the standard A major, it will probably feel resolved to you when you play the A. If you have a song with a number of bars of A major – switching between these two chords is a nice way to generate a little harmonic motion.

Now, I’ll take this idea a little further by lowering the A to a G#:

.

.

This gives the chord a 7 (G#), 9 (B), #11 (D#) and 13 (F#) – or all of the upper chord tones.

Short cut 2:

Playing a minor 7th chord on the seventh scale degree of a major chord will get you all of the upper extensions of the chord.

(i.e. G# minor 7 over A major)

Like the B7/A, this isn’t a stable sound on its own. If you play this chord and then the standard A major, it will probably feel resolved to you when you play the A.

.

Quartal for your thoughts?

Here’s one last transformation for now. Here I’m going to lower the D# to C# to create a quartal chord.

.

.

A quartal chord is a chord that is built on 4ths (G#, C#, F#, B) as opposed to being built on 3rds like A Major (A, C#, E). To me, quartal voicings have a nice “airy” or “floating” quality . This is just one of many possible quartal voicings built from A major. Quartal voicings will be discussed more in-depth in a future post.

.

How to double the number of chords that have been covered.

So far, I’ve looked at a series of chords that either work as substitutions and/or extensions for major chords I’m going to go into more depth about why this works in the next post but for right now – here’s a quick tip that gives a whole other dimension to using these chords.

.

Every chord presented here also works over the relative minor (i.e. F# minor chord).

.

Try taking this chord:

.

and after you play it add an F# by tapping a fret hand finger on the 2nd fret F# on the low E string for a very hip F# min 9 extension.

.

.

Hopefully this has given you some new chordal ideas!! You may want to go back to the first post and apply this idea by playing through all of the voicings covered there and adding the F# as a root.

In addition to explaining this approach more in-depth, in part 3 of these posts I’m going to explore a number of ways to use these ideas in your soloing.

Thanks for reading!! Please feel free to post any questions you might have.

-SC