Hey everyone,

As promised, here’s a follow-up lesson that takes the approach I explored in Part 13 and applies it to the Melodic Minor scale.

I’ll use C Melodic Minor in this case – but this idea will work on any root.

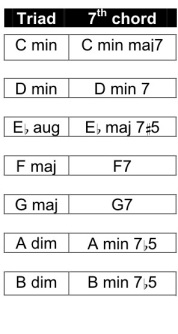

Chords

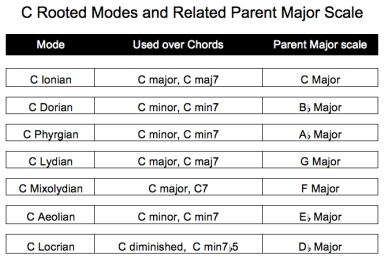

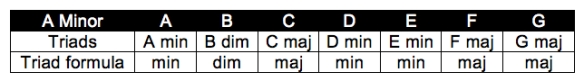

Before we get too far into the lick side of this let’s look at the chords to see what we can play this over.

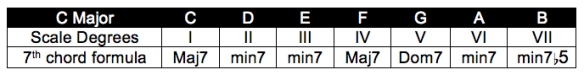

Here are the diatonic triads and 7th chords.

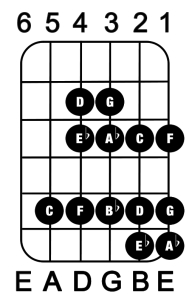

Try playing any of the following C Melodic Minor shapes over any of these chords..

Some Melodic Minor Notes:

- Melodic Minor is an old scale. Originally it was played as melodic minor when ascending but natural minor when descending. Not a whole lot of people perform it that way in Jazz circles but mixing and matching the two can have some interesting sounds (i.e. it’s something you should consider experimenting with if this area interests you and you haven’t already).

- Melodic Minor is a Dominant machine. If you check out the harmonization above you’ll see that Melodic Minor has two 7th chords in it’s harmonization. As Jazz standards use a LOT of dominant devices – this is a scale you’ll want to investigate if you have an even remote interest in Jazz.

- Melodic Minor is a weird sound. Yes it is. The I chord is a minor (maj7) chord and that whole b3 mixed with the natural 6th and 7th makes for some interesting moments. The only metal guy I knew who was really into that sound was David Chastain and he was doing instrumental stuff that didn’t really sound like anyone else. (Hint – this is worth exploring if you’re a rock or metal guy)

- Hip trick alert: since the ii chord is a minor chord -try playing C Melodic Minor lines over Bb Minor as well!

.

Now let’s talk about visualizing the scale.

“You take the good you take the bad – you flat the third and there you have…”

Melodic Minor

I’ve talked about my approach to Melodic Minor briefly in part 9 of this series – but as a brief review:

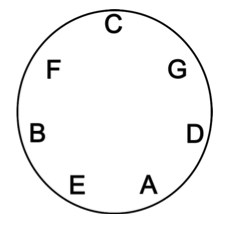

Major Scale/Modal Visualization Review

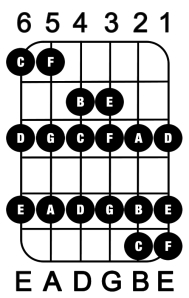

- The guitar fingerboard can be divided into 3 sets of two strings. Any 2-string fingering pattern that starts on the B string can be moved to the same starting pitch on the D or the low E string and keep the same fingering.

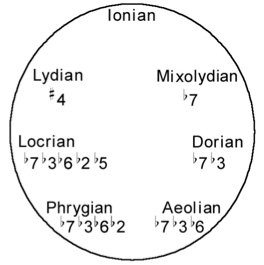

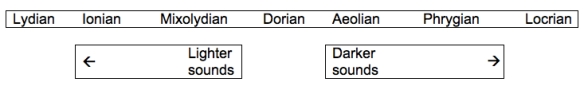

- The major scale can be broken down into seven two-string modes that follow a specific order based on its scale degree from the parent scale (Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian). The two-string patterns are modular and can be adapted to positional playing.

- Instead of thinking of individual modes when playing, I tend to think of larger tonal systems (i.e. I think of C Major all over the fingerboard instead of D Dorian or A Aeolian.)

- By thinking of the fingerboard in a larger scale – it makes it easier for me to navigate Melodic and Harmonic Minor as – solely from a fingering/sonic visualization standpoint – I just see it as variations of the Major scale patterns.

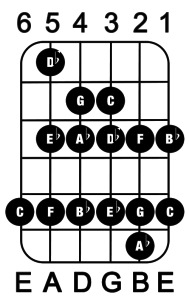

To visualize Melodic Minor patterns – simply flat the 3rd of the Parent Major scale. (i.e. to visualize C Melodic Minor just play C major but change every E to Eb).

It’s important to note that all of the fingering conventions mentioned here are solely to assist with visualization as Melodic and Harmonic Minor really aren’t directly related to the Major scale sonically.

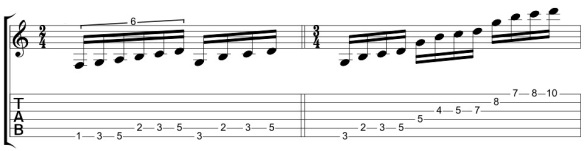

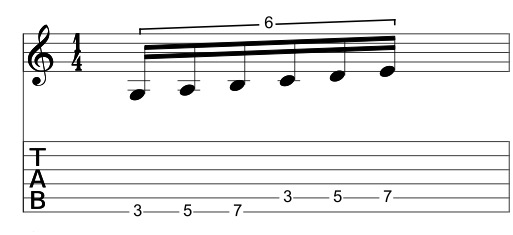

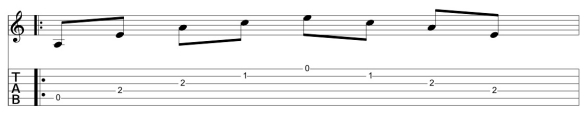

Here’s C Major

Here’s the audio.

Note:

In all the audio examples, I’ve played the example first as sextuplets – then at a slower tempo (i.e. 16ths) – then as sextuplets again.

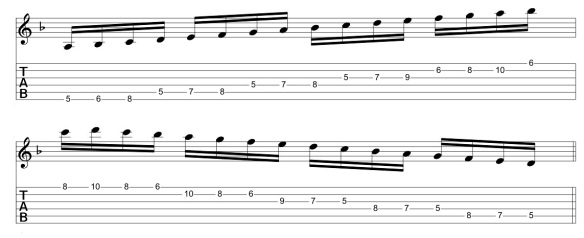

Here’s C Melodic Minor

(the only difference is that the E has been changed to Eb)

.

.

Melodic Minor short cuts:

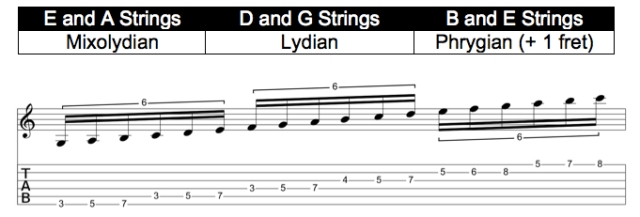

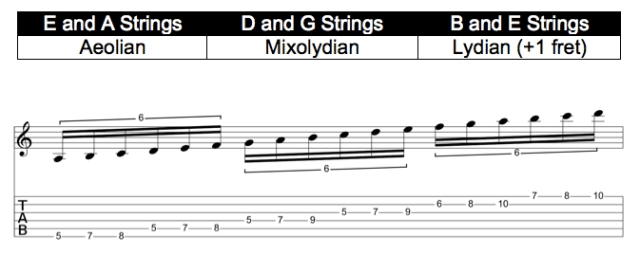

Using the Parent Major patterns above here’s a list of short cut’s to help you visualize the patterns.

.

Note: in the F Lydian shape – there’s no change from the major shape since there’s no Eb in the 2-string pattern.

.

.

.

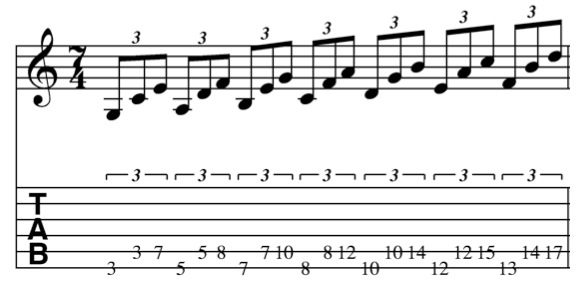

Not-Peggios

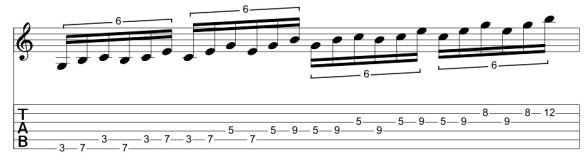

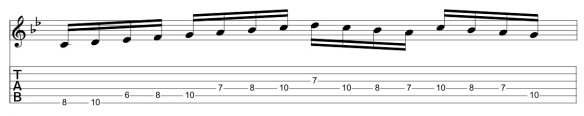

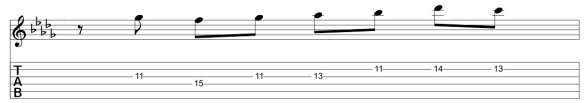

Now let’s take this not-peggio idea from the last lesson and apply it to C melodic minor starting from G.

In each of the following I’ll show the 2-string pattern followed by the 4-note “notpeggio” extraction from that fingering and then show the multi octave form.

Note: The extraction always starts from the second note of the 6-note pattern – so while the first example is extracted from the F Lydian fingering – it’s viewed as a G based pattern.

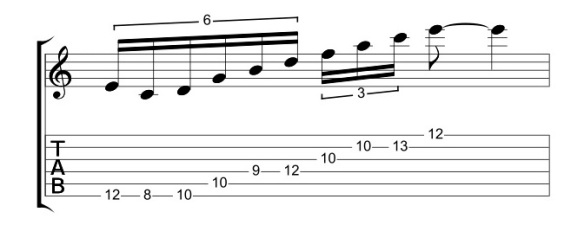

From G

Note: this G pattern is the same as the C major G shape.

From A

Note: this is a new shape from the Major patterns. The R-b3-4th-b5 shape may remind you of the A blues scale.

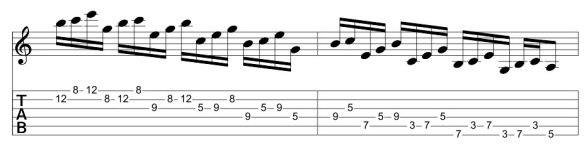

From B

Note: this is also a new shape from the Major patterns. The R-b3-b4th-b5 shape is something you may want to explore over diminished chords.

From C

Note: this C pattern shape is the same as the A minor form from C major.

From D

Note: this D pattern shape is also the same as the A minor form from C major. This shape and the C minor shape above on their own really won’t give you much of the Melodic Minor flavor on their own – but alternating between the two of them will. More on that in a future lesson.

From Eb

Note: this is a new shape from the Major patterns. The Eb Maj7 (#5) based pattern has been deconstructed into almost a whole-tone idea. This is one of my favorite “outside” sounds in this scale.

From F

Finally, this F pattern shape is the same as the F Lydian form from C major.

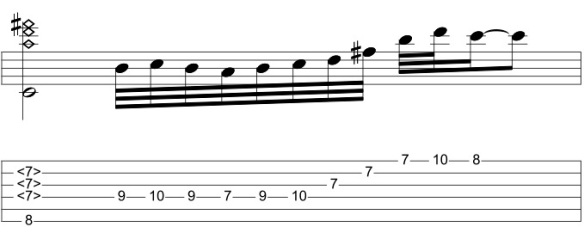

Here’s an audio sample of the 3/4 measures in ascending order from G